Le choléra est une maladie inhérente aux inégalités qui touche les populations les plus vulnérables.

Le choléra est une maladie diarrhéique aiguë causée par la bactérie Vibrio cholerae, qui peut entraîner la déshydratation et, dans les cas graves et non traités, la mort. Il existe plus d’une centaine de sérogroupes identifiés, mais seuls deux d’entre eux, O1 et O139, sont à l’origine d’épidémies. Il n’y a pas de différence dans la maladie causée par les deux sérogroupes.

Distribution d’eau à Hambourg lors de l’épidémie de choléra de 1892

Le choléra, bien que largement documenté depuis le XIXe siècle, sévit probablement depuis l’Antiquité. D’anciens textes médicaux indiens, comme le Sushruta Samhita (vers 500 avant notre ère) et le Charaka Samhita (vers 300 avant notre ère), décrivent des symptômes similaires à ceux du choléra. De même, des documents historiques chinois de la dynastie Han (entre l’an -206 et l’an 220) relatent des cas de maladies gastro-intestinales généralisées qui ont entraîné une forte mortalité, ressemblant à ce que nous connaissons aujourd’hui sous le nom de choléra. Des références au choléra apparaissent dans la littérature européenne dès 1642, dans la description du médecin hollandais Jakob de Bondt dans son ouvrage De Medicina Indorum.

La première pandémie de choléra documentée a débuté en 1817 et s’est propagée en Asie, au Moyen-Orient et dans certaines parties de l’Europe. En 1854, Filippo Pacini a isolé et identifié la bactérie du choléra, tandis que, la même année, John Snow identifiait son mode de transmission par l’eau, jetant ainsi les bases de l’épidémiologie moderne. Par la suite, six autres pandémies ont tué des millions de personnes sur tous les continents. La pandémie actuelle (la septième) a débuté en Asie du Sud en 1961, a atteint l’Afrique en 1971 et les Amériques en 1991. La septième pandémie de choléra est entrée dans une phase aiguë depuis 2021, et même des pays qui n’avaient pas connu d’épidémie récente commencent à signaler des cas.

Alors que le choléra a été éliminé d’Europe et d’Amérique du Nord depuis plus de 100 ans grâce à des investissements soutenus dans les infrastructures WASH, il continue d’affecter de manière disproportionnée les populations les plus pauvres et les plus vulnérables du monde.

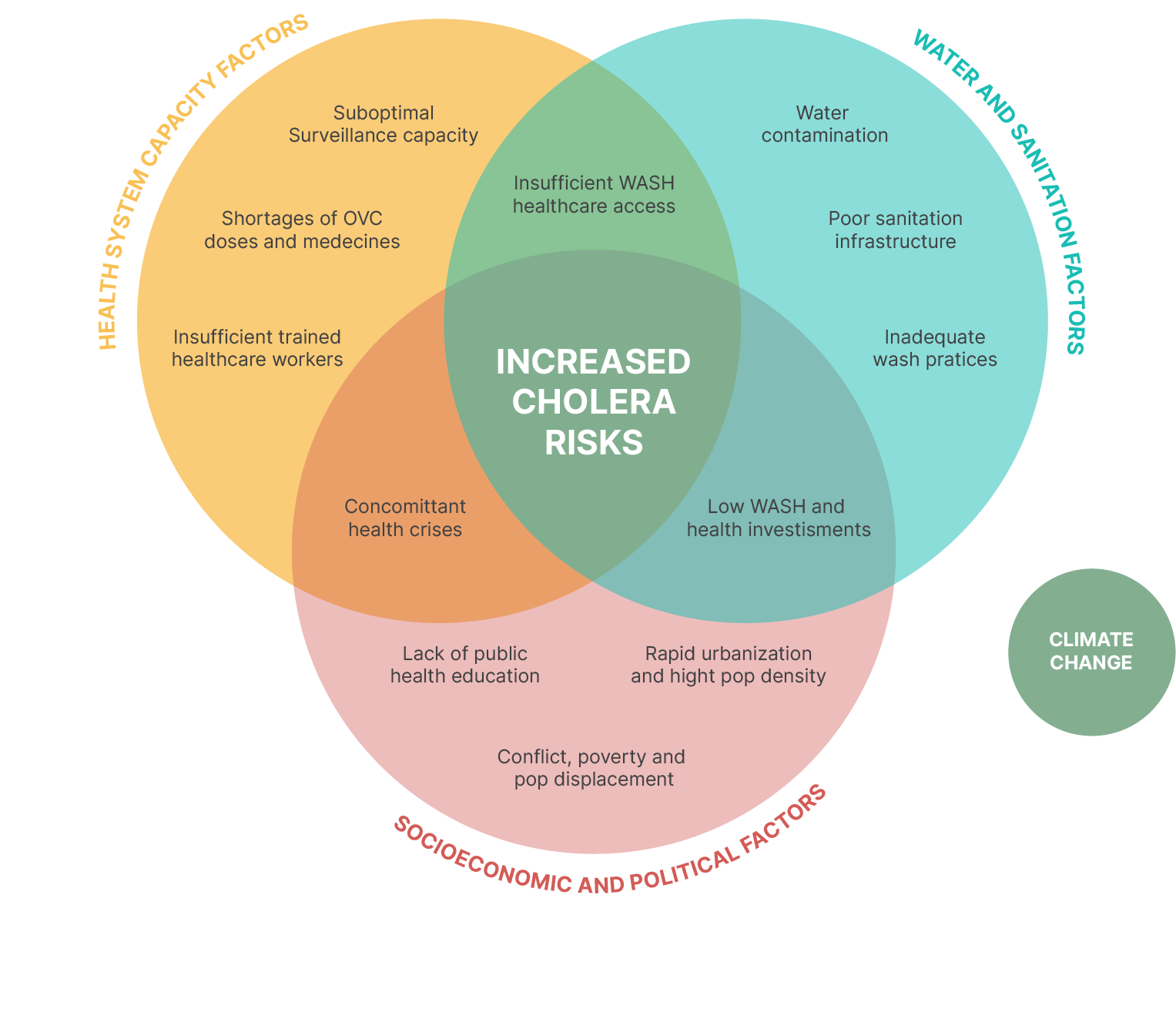

Au cours des 20 dernières années, le nombre de cas de choléra signalés par an dans le monde a varié entre 1,3 et 4 millions. Cependant, le choléra reste une maladie négligée et peu signalée, en partie à cause des limites des systèmes de surveillance, de la stigmatisation et de la crainte d’un impact sur le commerce ou le tourisme. Selon les estimations de l’OMS, le nombre réel de cas de choléra est jusqu’à quatre fois supérieur à celui des chiffres déclarés. La résurgence du choléra est due à l’interaction de multiples facteurs, ce qui rend complexe la lutte contre cette urgence.

La résurgence du choléra est due à l’interaction de multiples facteurs, ce qui rend complexe la lutte contre cette urgence.

Le choléra se propage principalement par l’eau et les aliments contaminés par Vibrio cholerae. La bactérie se développe dans des conditions d’hygiène insuffisantes, en particulier dans les milieux vulnérables, où les sources d’eau et de nourriture peuvent être compromises. La maladie a une courte période d’incubation (à savoir entre deux heures et cinq jours) et peut rapidement dégénérer en foyers de grande ampleur si elle n’est pas rapidement maîtrisée. Le choléra peut être contracté à tout âge.

Le choléra peut être endémique ou épidémique. Une zone endémique pour le choléra est une zone où des cas confirmés de choléra ont été détectés au cours des trois dernières années, avec des preuves de transmission locale (ce qui signifie que les cas ne sont pas importés d’ailleurs). Une épidémie de choléra peut survenir à la fois dans les pays endémiques et dans les pays où le choléra ne sévit pas régulièrement.

La plupart des cas peuvent être traités avec succès à l’aide d’un soluté de réhydratation orale (SRO), mais les cas graves nécessitent l’administration de fluides et/ou d’antibiotiques par voie intraveineuse.

Si la plupart des personnes infectées par Vibrio cholerae ne présentent que des symptômes bénins, une proportion importante d’entre elles développera une déshydratation sévère pouvant conduire à un choc hypovolémique et à la mort en quelques heures, en l’absence de traitement.

Le choléra peut être évité grâce aux outils dont nous disposons aujourd’hui ; l’objectif de son éradication est donc à portée de main.

Les vaccins oraux contre le choléra ont révolutionné la lutte contre cette maladie. Les OCV procurent une protection immédiate et sont efficaces pendant 2 à 3 ans ; ils sont une passerelle cruciale entre les interventions d’urgence et la lutte à long terme contre le choléra qui se concentre sur l’eau, l’assainissement et l’hygiène (WASH). Depuis que l’OMS a constitué une réserve d’OCV en 2013, plus de 184 millions de doses ont été livrées à 33 pays, ce qui a permis de réduire considérablement l’impact des épidémies de choléra.

Des efforts supplémentaires sont nécessaires pour répondre aux besoins des pays en matière de campagnes de vaccination réactives et préventives. Depuis 2022, les stocks actuels et les capacités de production de vaccins ne permettent plus d’organiser des campagnes de prévention. Des stratégies de vaccination à dose unique ont été mises en place pour pallier les pénuries actuelles.

Le choléra est une maladie transmise par l’eau. Pourtant, 1,8 milliard de personnes vivent dans des foyers ne disposant pas d’un accès adéquat à l’eau potable et à l’assainissement, ce qui les met en danger. Garantir un accès digne et sûr à l’eau est une condition préalable à l’élimination du choléra et d’autres maladies d’origine hydrique.

L’investissement dans les programmes WASH est essentiel pour protéger les personnes exposées au choléra et répondre aux besoins de base en matière d’approvisionnement en eau, d’assainissement et d’hygiène au niveau des ménages et des communautés (écoles, marchés, etc.) ainsi qu’au sein des établissements de soins de santé.

L’implication des communautés fait partie intégrante de la prévention et de la lutte contre le choléra. Faire participer les populations à l’élaboration et à la mise en œuvre des programmes, c’est assurer le respect des cultures, des pratiques et des croyances locales, et promouvoir ainsi des actions efficaces et de bonnes pratiques d’hygiène, comme le lavage des mains au savon, la préparation et le stockage sûrs des aliments, et l’adaptation des pratiques funéraires pour prévenir la transmission du choléra.

Pendant les épidémies, l’implication de la communauté est essentielle pour sensibiliser la population aux risques du choléra, à ses symptômes et aux précautions à prendre. Les populations doivent participer activement à la création de programmes qui répondent à leurs besoins spécifiques, notamment pour savoir où et quand il convient de demander un traitement.

La surveillance du choléra doit faire partie d’un système intégré de surveillance des maladies qui comprend un retour d’information au niveau local et un partage des informations au niveau mondial. Des efforts supplémentaires sont nécessaires pour détecter et confirmer rapidement les épidémies de choléra et pour les surveiller efficacement afin de mieux orienter les interventions multisectorielles. Il faut pour cela moderniser le système d’information, renforcer les capacités et décentraliser les capacités de test.

La rapidité d’accès au traitement est essentielle lors d’une épidémie de choléra. La réhydratation orale devrait être à disposition des populations, notamment dans des points de réhydratation orale (ORP) spécifiques, en plus des grands centres de traitement qui peuvent fournir des liquides intraveineux et des soins 24 heures sur 24. Grâce à un traitement précoce et approprié, le taux de létalité devrait rester inférieur à 1 %.

La prise en charge actuelle des cas de choléra présente des lacunes importantes qui doivent être comblées de toute urgence. Il s’agit notamment d’un accès inadéquat à un traitement rapide et efficace dans les régions éloignées ou disposant de ressources limitées, d’une disponibilité insuffisante de sels de réhydratation orale (SRO) et de liquides intraveineux, et du manque de personnel de santé formé pour gérer efficacement les épidémies de choléra. En outre, il est nécessaire de mieux intégrer la prise en charge des cas dans les systèmes de soins de santé au sens large afin de garantir une réponse rapide en cas d’épidémie.

La recherche sur le choléra a fait des progrès considérables, mais il reste des lacunes critiques qui nécessitent une attention urgente. Les efforts de recherche actuels ont permis d’améliorer notre compréhension de la maladie, la mise au point de vaccins et les stratégies de traitement, mais beaucoup reste encore à faire pour relever les défis persistants. Les principaux domaines nécessitant des recherches supplémentaires comprennent le développement de vaccins plus efficaces et plus durables, la compréhension des facteurs environnementaux et sociaux à l’origine des épidémies et l’amélioration des outils de diagnostic rapide pour une détection précoce. En outre, il est nécessaire de mener davantage de recherches opérationnelles afin d’optimiser la mise en œuvre des programmes de lutte contre le choléra dans divers contextes. Il est essentiel de donner la priorité à ces domaines de recherche pour faire progresser les efforts d’élimination du choléra dans le monde.